Only the River Flows: A Twilight for an Arthouse China, or another Illusion?

By Weiqing Chen

An Unimpressive End-of-Year Surprise

It was December 31st, 2018. Tens of thousands of moviegoers trooped into theaters around mainland China for the premiere of the much anticipated film Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Director Bi Gan shocked the arthouse film circle with his debut Kaili Blues in 2015. He was regarded as the Tarkovsky, Tsai Ming-liang, and Apichatpong of China, and more importantly, a promising herald of a new generation of arthouse film directors. Most of the audience who joined on this chilly last day of the year, however, did not know who Bi was, and did not know much about arthouse cinema. They were attracted instead by the film’s promotional slogan, “a kiss across the (new) year.” They were promised that, towards the film’s end, at the closure of its signature 60-minute long take, the leading actors Tang Wei and Huang Jue would kiss each other, exactly as the first seconds of 2019 seeped in.

Long Day set a new national box office record for arthouse films in China, but at a high cost. After grossing 37 million USD on its first day, the film closed its mainland release about one month later with a meager growth of only 2.5 million USD. Bi’s extremely slow cinematic rhythm, stream-of-consciousness narrative, and abstruse poetic voiceovers meant that the majority of moviegoers - unaware of the film’s arthouse nature and had instead anticipated a commercial romance film - could not stand him. “Unbearably pretentious, unreasonably long and sleep inducing…” Negative reviews of Long Day gave Bi so much backlash, that he is still yet to be able to kickstart his third full-length film as of today.

Behind the Scenes: The Arthouse Conundrum

Long Day’s distribution strategy became an iconic case study for film production students. There is no doubt that its camouflage as a commercial film is a double-edged sword. Through a producing point of view, it flattered the market enough to make a profit. On the other hand, reviews from a market that is not ready for large scale appreciation of arthouse films hampered creative efforts of the film’s cast and crew. It reveals the frustrating fact that, without a market division between arthouse and commercial cinema in China, domineering presence of commercial films leave arthouse films little room for profit in domestic theater release.

As early as of 2006, Jia Zhangke’s arthouse Still Life (Good People of the Three Gorges), despite being the first Chinese film that won the Golden Lion at Venice Film Festival, faced a debilitating box office defeat against Zhang Yimou’s blockbuster Cruise of the Golden Flower. “I want to see how many of us would still care about the ‘good people’ in an era of gold fetishism.” Jia’s idealism was formidable, but could not salvage the unsatisfactory performances of Chinese arthouse films’ theater releases.

Numerous factors have contributed to the lack of arthouse and commercial division in China. At the turn of the 21st century, pirated DVDs and VCDs cultivated a cinephile culture for Euro-American arthouse films, as pirates exhausted all technical means to dub films with the highest quality, and buyers went on shopping sprees “like drug addicts” at electronic markets in every city they visited. The inception of arthouse cinema in China, therefore, was characterized by an underground implication. Many arthouse directors, such as Jia Zhangke, gained greater fame for shooting the “banned” films, which circulated informally in clandestine DVD shops or online drives. Jia himself recounted an intriguing anecdote, where a seller urged him to check out the newly obtained DVD of Platform, directed by a certain “Section Chief Jia.” Platform, indeed, was Jia’s own second full-length film.

Since it could take many years for arthouse films to get screening permits in mainland (or alternatively, very possibly, rejections), most arthouse producers learned to place their hopes in overseas distribution. Domestic distributions, if there were any, are often characterized by small-scale test screenings featuring selected, elite centered audiences and film critics specializing in arthouse reviews.

A Glimmer of Hope… And Its Shadows

Five years after Long Day’s failure to sustain its opening night success, the month of December 2023 may have signaled a historical moment for Chinese arthouse cinema. On December 5th, Wei Shujun’s third full-length film Only the River Flows earned 42 million USD at the box office, marking a new national record. More importantly, the impressive data was not obtained through any head-heavy hysteria, as with Long Day. Instead, River’s revenue steadily grew from the 7.4 million USD that concluded its first date of release (October 21, 2023). In contrast to Long Day, River also did not have to wear the camouflage of the commercial genre, but openly promoted itself as an arthouse avant-garde film. Overall, the success of River seemed to paint an optimistic picture for Chinese arthouse films: more timely domestic releases, engaged audiences and supportive creative environments appeared to be on the horizon.

But is River’s success replicable? On a closer look, arthouse films that were in theaters around the same times of the year, including Wei’s own second full-length Ripples of Life and renowned Singaporean director Anthony Chen’s The Breaking Ice, were still discouraged by flopping box office data. It seems River’s success may have been the merry confluence of exceptionally rare chances.

The feature that separates River fundamentally from other arthouse films is its incorporation of a celebrity actor with a tremendous fan base. Zhu Yilong, who went viral across China after starring in two blockbuster net series, plays the main role in Wei’s film. Many of River’s promotions take advantage of the young actor’s fame, foregrounding his stills and hashtags. At the same time, starring in River also serves Zhu’s interest well, given that venturing into the arthouse world is a conventional tactic for celebrity actors to “level up” their “inferior” status as web series actors. Fan culture provided opportunities of exposure and discourse building that proved to be a luxury in the sphere of arthouse cinema. Granted, many arthouse films have previously incorporated similar strategies and tasted bitter results, given the stereotypical (and to various extents true) impression of celebrity actors’ lack of professionality. Zhu’s relative professionality may have saved him and the film from similar backlash.

On a more subtle note, River, adapted from a novella of the same name, also gleaned tremendous commercial benefits from the literary world. The author of this novella is no other than Yu Hua, who penned arguably the most well-known modern Chinese novel, To Live, often said to spiritually encapsulate generations of Chinese lives. This novel was adapted by Zhang Yimou in 1994: the film screened at New York Film Festival, became incorporated into China-related curriculums across the US, and reached international fame, but was denied theatrical release in mainland China. Over the past three decades, Yu has grown from a renowned author to someone that approximates a “public intellectual,” assuming tremendous online and in-person presence, ranging from university lectures, advertisements, to book release tours of his old-time classmate, China’s first Nobel literature prize laureate Mo Yan.

In contrast to To Live, which features plain language and a straight-forward narrative that helps enable its wide reach across China, Yu’s novellas are little known to non-specialists because of their obscurity and experimental nature. Perhaps hoping to boost the visibility of his novellas, Yu actively participated in River’s promotion tours. Like Zhu, he is an exceptional figure, whose “big name” can foster phenomenality rarely seen in arthouse circles. Additionally, Yu’s simultaneous status as “high” literary figure and amiable public figure balances arthouse films’ notoriety for pretentiousness and their paradoxical desire to reach the sinking markets.

Is River, then, a watershed moment for Chinese arthouse cinema, or a one time phenomenon that only stirs illusionistic optimism? Time will tell. In the meantime, it is undeniable that without concrete structural changes within the industry, increasingly adaptive distribution strategies alone are not enough to foster stable presence and viewership of arthouse films in China.

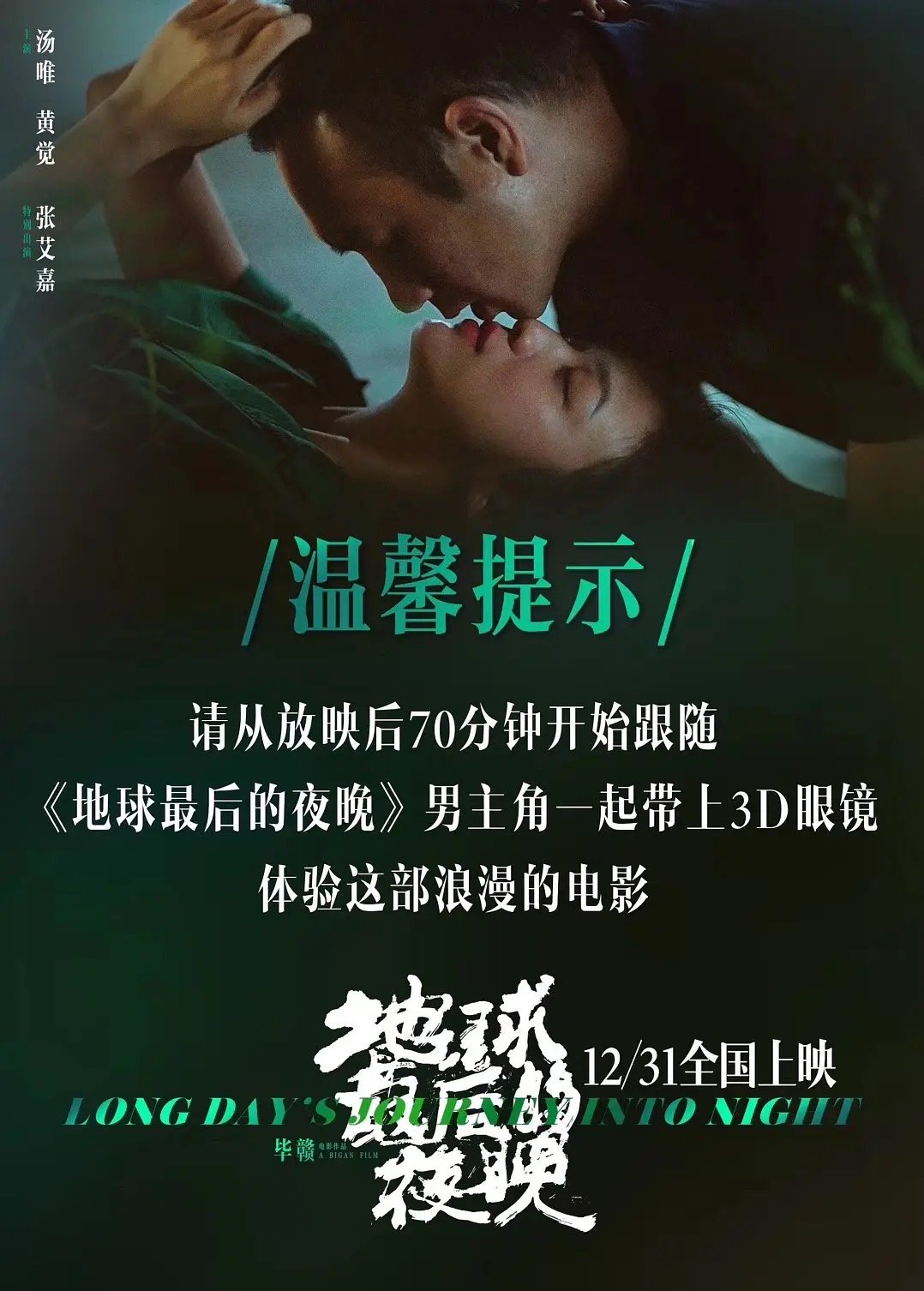

“Starting from the 70th minute, please put on 3D glasses with the male leading actor, and enjoy this romantic film.” This poster emphasizes another promotional strategy that is not mentioned in the main article - the inception of 3D technology in the middle of the film

This poster features the slogan “a kiss across the (new) year,” and an expert from Bi Gan’s poems. This would be the most relevant poster, but the visuals are less engaging.

A “luxury” version of pirated DVD of The Last Emperor (dir. Bertolucci), copied from Criterion Collection’s release of a similar set of DVDs in 2010

The main poster of Only the River Flows. Note the relative prominence of Zhu Yilong’s face in contrast to other figures, and the placement of the line “Adapted from Yu Hua’s Novella of the Same Name” above Wei Shujun’s designation as director (“A Wei Shujun Film”)

Stills from Zhang Yimou’s 1994 adaptation of Yu Hua’s To Live, starring Ge You and Gong Li

Yu Hua (2nd right) and Zhu Yilong (4th right) at a promotion tour of Only the River Flows, with director Wei Shujun (3rd right)

Yu Hua (right) and Mo Yan (left), lovingly mocked by Chinese netizens